The pandemic and the COVID-19 crisis have undoubtedly made visible and exposed the historical inequalities between men and women in terms of domestic work and care tasks. How can we understand the double role and exploitation experienced by women in the current crisis?

For Valentina Álvarez, post-doctoral researcher at the University of Valparaíso, “the pandemic intensified the privatization of care, which until before the confinement took place in the home. And we say ‘intensified’ because it is in capitalism that the family has been nuclearized“. This is because with the closure of crèches, kindergartens, and schools, as well as restrictions on access and priorities in health centers redirected to COVID-19 treatment, households were pressured to make decisions and take responsibility for the care needs of children and the sick, adds the sociology doctor.

The data has been clear, the responsibility for care tasks fell mostly on women. According to Álvarez, this is “a consequence both of the way in which confinement affected the economy and the labor market, and of the cultural construction of gender, which, from the point of view of the theory of social reproduction, has been shown to be deeply intertwined“.

If we analyze the whole scenario, we see that the economic activities most affected by the pandemic were those where there is a greater female occupation and where there is direct contact with people, such as accommodation and food services, commerce, and paid domestic work. So much so that ECLAC has denounced the decline in female employment in the region over the last decade. “Despite this, unemployment was higher among men, precisely because confinement meant that women withdrew from the labor force, i.e., they did not look for work“, explains the expert on gender and social production/reproduction.

Studies on women’s work show that, “for decades, care work has appeared as one of the big backpacks that women carry and that hinder their incorporation into the labor market“, comments Álvarez, adding that, “it is a moment that allows us to discuss again certain statements that have been present in different moments of Marxist feminism: women as a reserve army of the labor market, or the need to socialize care work to allow for an equal incorporation into this market“.

On the other hand, the INE’s 2015 National Time Use Survey objectively reported something that we as women know from our daily experience: it is mostly women who dedicate more than twice as many hours (and bear more responsibility) to domestic and care work than men, regardless of whether they work for pay or not. However, the pandemic has increased the amount of work. “The pandemic has imposed new demands in terms of accompanying children’s education, for example with homework or online classes, intensified care for the elderly and the sick, and increased the demands of domestic hygiene, among other things“, says Valentina Álvarez, for whom it is not surprising that women are among the groups most affected in terms of mental health because of the pandemic.

However, for Álvarez, a member of the Feminist Studies Group, in the context of neoliberal capitalism (and globalization), the working class is experiencing a process of feminization in another sense: poorer quality work that has historically been available to migrants with fewer rights or women, because their ability to bear children and breastfeed has positioned them unfavorably in the labor market, has become widespread.

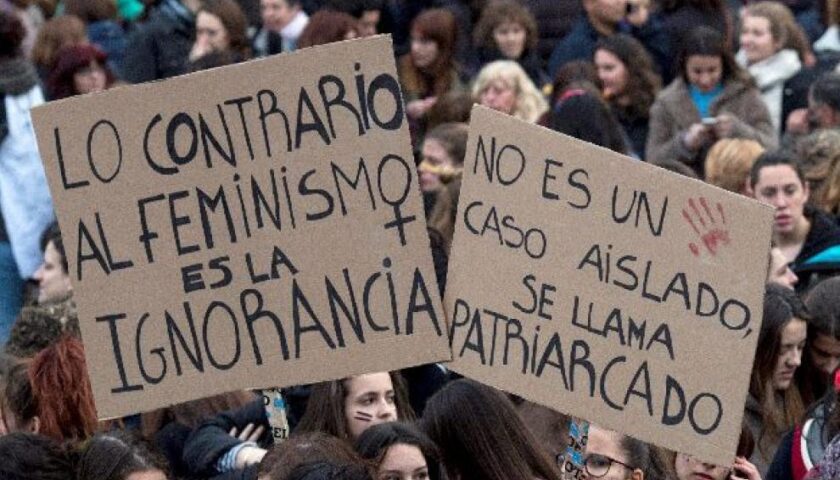

Along these lines, and thinking about the challenges ahead, for the IIPSS researcher it is important: “to emphasize the theoretical and political power of contemporary feminism in its struggle and denunciation against the precariousness of life, a precariousness that is already violent, and which increases gender violence even more. Today, it is no longer possible to think feminism without anti-racism, environmentalism, pluractionality. This feminist wave in which we find ourselves is, as my colleagues say, the contemporary form of the historical struggles of the working class“, concludes Álvarez.